Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan | |

|---|---|

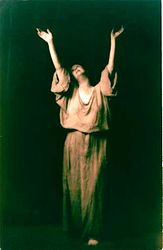

Duncan c. 1906–1912 | |

| Born | Angela Isadora Duncan May 26, 1877[a] San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | September 14, 1927 (aged 50)[a] Nice, France |

| Citizenship | American, French, Soviet |

| Known for | Dance and choreography |

| Movement | Modern/contemporary dance |

| Spouse | |

| Partner(s) | Edward Gordon Craig Paris Singer Romano Romanelli Mercedes de Acosta |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

Angela Isadora Duncan (May 26, 1877, or May 27, 1878[a] – September 14, 1927) was an American-born dancer and choreographer, who was a pioneer of modern contemporary dance and performed to great acclaim throughout Europe and the United States. Born and raised in California, she lived and danced in Western Europe, the U.S., and Soviet Russia from the age of 22. She died when her scarf became entangled in the wheel and axle of the car in which she was travelling in Nice, France.[2]

Early life

[edit]Angela Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco, the youngest of the four children of Joseph Charles Duncan (1819–1898), a banker, mining engineer and connoisseur of the arts, and Mary Isadora Gray (1849–1922). Her brothers were Augustin Duncan and Raymond Duncan;[3] her sister, Elizabeth Duncan, was also a dancer.[4][5] Soon after Isadora's birth, her father was found to have been using funds from two banks he had helped set up to finance his private stock speculations. Although he avoided prison time, Isadora's mother (angered over his infidelities as well as the financial scandal) divorced him, and from then on the family struggled with poverty.[3] Joseph Duncan, along with his third wife and their daughter, died in 1898 when the British passenger steamer SS Mohegan ran aground off the coast of Cornwall.[6]

After her parents' divorce,[7] Isadora's mother moved with her family to Oakland, California, where she worked as a seamstress and piano teacher. Isadora attended school from the ages of six to ten, but she dropped out, having found it constricting. She and her three siblings earned money by teaching dance to local children.[3]

In 1896, Duncan became part of Augustin Daly's theater company in New York, but she soon became disillusioned with the form and craved a different environment with less of a hierarchy.[8]

Work

[edit]

Duncan's novel approach to dance had been evident since the classes she had taught as a teenager, where she "followed [her] fantasy and improvised, teaching any pretty thing that came into [her] head".[9] A desire to travel brought her to Chicago, where she auditioned for many theater companies, finally finding a place in Augustin Daly's company. This took her to New York City where her unique vision of dance clashed with the popular pantomimes of theater companies.[10] While in New York, Duncan also took some classes with Marie Bonfanti but was quickly disappointed by ballet routine.

Feeling unhappy and unappreciated in America, Duncan moved to London in 1898. She performed in the drawing rooms of the wealthy, taking inspiration from the Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum.[11][12] The earnings from these engagements enabled her to rent a studio, allowing her to develop her work and create larger performances for the stage.[13] From London, she traveled to Paris, where she was inspired by the Louvre and the Exposition Universelle of 1900 and danced in the salons of Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux and Princesse Edmond de Polignac.[14] In France, as elsewhere, Duncan delighted her audience.[15]

In 1902, Loie Fuller invited Duncan to tour with her. This took Duncan all over Europe as she created new works using her innovative technique,[16] which emphasized natural movement in contrast to the rigidity of traditional ballet.[17] She spent most of the rest of her life touring Europe and the Americas in this fashion.[18] Despite mixed reaction from critics, Duncan became quite popular for her distinctive style and inspired many visual artists, such as Antoine Bourdelle, Dame Laura Knight, Auguste Rodin, Arnold Rönnebeck, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, and Abraham Walkowitz, to create works based on her.[19]

In 1910, Duncan met the occultist Aleister Crowley at a party, an episode recounted by Crowley in his Confessions.[20] He refers to Duncan as "Lavinia King", and used the same invented name for her in his 1929 novel Moonchild (written in 1917). Crowley wrote of Duncan that she "has this gift of gesture in a very high degree. Let the reader study her dancing, if possible in private than in public, and learn the superb 'unconsciousness' – which is magical consciousness – with which she suits the action to the melody."[21] Crowley was, in fact, more attracted to Duncan's bohemian companion Mary Dempsey (a.k.a. Mary D'Este or Desti), with whom he had an affair. Desti had come to Paris in 1901 where she soon met Duncan, and the two became inseparable. Desti, who also appeared in Moonchild (as "Lisa la Giuffria") and became a member of Crowley's occult order,[b] later wrote a memoir of her experiences with Duncan.[22]

In 1911, the French fashion designer Paul Poiret rented a mansion – Pavillon du Butard in La Celle-Saint-Cloud – and threw lavish parties, including one of the more famous grandes fêtes, La fête de Bacchus on June 20, 1912, re-creating the Bacchanalia hosted by Louis XIV at Versailles. Isadora Duncan, wearing a Greek evening gown designed by Poiret,[23] danced on tables among 300 guests; 900 bottles of champagne were consumed until the first light of day.[23]

Opening schools of dance

[edit]Duncan disliked the commercial aspects of public performance, such as touring and contracts, because she felt they distracted her from her real mission, namely the creation of beauty and the education of the young.[citation needed] To achieve her mission, she opened schools to teach young girls her philosophy of dance. The first was established in 1904 in Berlin-Grunewald, Germany. This institution was in existence for three years and was the birthplace of the "Isadorables" (Anna, Maria-Theresa, Irma, Liesel, Gretel, and Erika[24]), Duncan optimistically dreamed her school would train “thousands of young dancing maidens” in non-professional community dance.[25] It was a boarding school that in addition to a regular education, also taught dance but the students were not expected or even encouraged to be professional dancers.[26] Duncan did not legally adopt all six girls as is commonly believed.[27] Nevertheless, three of them (Irma, Anna and Lisa) would use the Duncan surname for the rest of their lives.[28][29] After about a decade in Berlin, Duncan established a school in Paris that soon closed because of the outbreak of World War I.[30]

In 1914, Duncan moved to the United States and transferred her school there. A townhouse on Gramercy Park in New York was provided for its use, and its studio was nearby, on the northeast corner of 23rd Street and Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South).[31] Otto Kahn, the head of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., gave Duncan use of the very modern Century Theatre at West 60th Street and Central Park West for her performances and productions, which included a staging of Oedipus Rex that involved almost all of Duncan's extended entourage and friends.[32] During her time in New York, Duncan posed for studies by the photographer Arnold Genthe.

Duncan had planned to leave the United States in 1915 aboard the RMS Lusitania on its ill-fated voyage, but historians believe her financial situation at the time drove her to choose a more modest crossing.[33] In 1921, Duncan's leftist sympathies took her to the Soviet Union, where she founded a school in Moscow. However, the Soviet government's failure to follow through on promises to support her work caused her to return[when?] to the West and leave the school to her protégée Irma.[34] In 1924, Duncan composed a dance routine called Varshavianka to the tune of the Polish revolutionary song known in English as Whirlwinds of Danger.[35]

Philosophy and technique

[edit]

Breaking with convention, Duncan imagined she had traced dance to its roots as a sacred art.[36] She developed from this notion a style of free and natural movements inspired by the classical Greek arts, folk dances, social dances, nature, and natural forces, as well as an approach to the new American athleticism which included skipping, running, jumping, leaping, and tossing.[citation needed] Duncan wrote of American dancing: "let them come forth with great strides, leaps and bounds, with lifted forehead and far-spread arms, to dance."[37] Her focus on natural movement emphasized steps, such as skipping, outside of codified ballet technique.

Duncan also cited the sea as an early inspiration for her movement,[38] and she believed movement originated from the solar plexus.[39] Duncan placed an emphasis on "evolutionary" dance motion, insisting that each movement was born from the one that preceded it, that each movement gave rise to the next, and so on in organic succession. It is this philosophy and new dance technique that garnered Duncan the title of the creator of modern dance.

Duncan's philosophy of dance moved away from rigid ballet technique and towards what she perceived as natural movement. She said that in order to restore dance to a high art form instead of merely entertainment, she strove to connect emotions and movement: "I spent long days and nights in the studio seeking that dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body's movement."[39] She believed dance was meant to encircle all that life had to offer—joy and sadness. Duncan took inspiration from ancient Greece and combined it with a passion for freedom of movement. This is exemplified in her revolutionary costume of a white Greek tunic and bare feet. Inspired by Greek forms, her tunics also allowed a freedom of movement that corseted ballet costumes and pointe shoes did not.[40] Costumes were not the only inspiration Duncan took from Greece: she was also inspired by ancient Greek art, and utilized some of its forms in her movement (as shown on photos).[41]

Personal life

[edit]

Children

[edit]Duncan bore three children, all out of wedlock.

Deirdre Beatrice was born September 24, 1906. Her father was theatre designer Gordon Craig. Patrick Augustus was born May 1, 1910,[42] fathered by Paris Singer, one of the many sons of sewing machine magnate Isaac Singer. Deirdre and Patrick both died by drowning in 1913. While out on a car ride with their nanny, the automobile accidentally went into the River Seine.[42] Following this tragedy, Duncan spent several months on the Greek island of Corfu with her brother and sister, then several weeks at the Viareggio seaside resort in Italy with actress Eleonora Duse.

In her autobiography, Duncan relates that in her deep despair over the deaths of her children, she begged a young Italian stranger, the sculptor Romano Romanelli, to sleep with her because she was desperate for another child.[43] She gave birth to a son on August 13, 1914, but he died shortly after birth.[44][45]

Relationships

[edit]When Duncan stayed at the Viareggio seaside resort with Eleonora Duse, Duse had just left a relationship with the rebellious and epicene young feminist Lina Poletti. This fueled speculation as to the nature of Duncan and Duse's relationship, but there has never been any indication that the two were involved romantically.

Duncan was loving by nature and was close to her mother, siblings and all of her male and female friends.[46] Later on, in 1921, after the end of the Russian Revolution, Duncan moved to Moscow, where she met the poet Sergei Yesenin, who was eighteen years her junior. On May 2, 1922, they married, and Yesenin accompanied her on a tour of Europe and the United States. However, the marriage was brief as they grew apart while getting to know each other. In May 1923, Yesenin returned to Moscow. Two years later, on December 28, 1925, he was found dead in his room in the Hotel Angleterre in Leningrad (formerly St Petersburg and Petrograd), in an apparent suicide.[47]

Duncan also had a relationship with the poet and playwright Mercedes de Acosta, as documented in numerous revealing letters they wrote to each other.[48] In one, Duncan wrote, "Mercedes, lead me with your little strong hands and I will follow you – to the top of a mountain. To the end of the world. Wherever you wish."[49]

However, the claim of a purported relationship made after Duncan’s death by de Acosta (a controversial figure for her alleged relations) is in dispute.[50][51][52][53] Friends and relatives of Duncan believed her claim is false based on forged letters and done for publicity’s sake.[54] In addition, Lily Dikovskaya, one of Duncan’s students from her Moscow School, wrote in In Isadora’s Steps that Duncan “was focused on higher things”.[54]

Later years

[edit]By the late 1920s, Duncan, in her late 40s, was depressed by the deaths of her three young children. She spent her final years financially struggling, moving between Paris and the Mediterranean, running up debts at hotels. Her autobiography My Life was published in 1927 shortly after her death. The Australian composer Percy Grainger called it a "life-enriching masterpiece."[55]

In his book Isadora, An Intimate Portrait, Sewell Stokes, who met Duncan in the last years of her life, described her extravagant waywardness. In a reminiscent sketch, Zelda Fitzgerald wrote how she and her husband, author F. Scott Fitzgerald, sat in a Paris cafe watching a somewhat drunken Duncan. He would speak of how memorable it was, but all that Zelda recalled was that while all eyes were watching Duncan, she was able to steal the salt and pepper shakers from the table.[56]

Death

[edit]

On September 14, 1927, in Nice, France, Duncan was a passenger in an Amilcar CGSS automobile owned by Benoît Falchetto, a French-Italian mechanic. She wore a long, flowing, hand-painted silk scarf, created by the Russian-born artist Roman Chatov, a gift from her friend Mary Desti, the mother of American filmmaker, Preston Sturges. Desti, who saw Duncan off, had asked her to wear a cape in the open-air vehicle because of the cold weather, but she would agree to wear only the scarf.[57] As they departed, she reportedly said to Desti and some companions, "Adieu, mes amis. Je vais à la gloire! " ("Farewell, my friends. I go to glory!"); but according to the American novelist Glenway Wescott, Desti later told him that Duncan's actual parting words were, "Je vais à l'amour" ("I am off to love"). Desti considered this embarrassing, as it suggested that she and Falchetto were going to her hotel for a tryst.[58][59][60]

Her silk scarf, draped around her neck, became entangled in the wheel well around the open-spoked wheels and rear axle, pulling her from the open car and breaking her neck.[2] Desti said she called out to warn Duncan about the scarf almost immediately after the car left. Desti took Duncan to the hospital, where she was pronounced dead.[57]

As The New York Times noted in its obituary, Duncan "met a tragic death at Nice on the Riviera". "According to dispatches from Nice, Duncan was hurled in an extraordinary manner from an open automobile in which she was riding and instantly killed by the force of her fall to the stone pavement."[61] Other sources noted that she was almost decapitated by the sudden tightening of the scarf around her neck.[62] The accident gave rise to Gertrude Stein's remark that "affectations can be dangerous".[63] At the time of her death, Duncan was a Soviet citizen. Her will was the first of a Soviet citizen to undergo probate in the U.S.[64]

Duncan was cremated, and her ashes were placed next to those of her children[65] in the columbarium at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[66] On the headstone of her grave is inscribed École du Ballet de l'Opéra de Paris ("Ballet School of the Opera of Paris").

Works

[edit]- Duncan, Isadora (1927) "My Life" New York City: Boni & Liveright OCLC 738636

- Project Gutenberg Canada #941 HTML HTML zipped Text Text zipped EPUB

- My Life at Faded Page (Canada) : text, HTML, EPUB, .mobi, PDF, HTML .zip

- Duncan, Isadora; Cheney, Sheldon (ed.) The Art of the Dance. New York: Theater Arts, 1928. ISBN 0-87830-005-8

- Works by Isadora Duncan at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Isadora Duncan at Open Library

Legacy

[edit]

Duncan is known as "The Mother of Dance". While her schools in Europe did not last long, Duncan's work had an impact on the art and her style is still danced based upon the instruction of Maria-Theresa Duncan,[67] Anna Duncan,[68] and Irma Duncan,[69] three of her six pupils. Through her sister, Elizabeth, Duncan's approach was adopted by Jarmila Jeřábková from Prague where her legacy persists.[70] By 1913 she was already being celebrated. When the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was built, Duncan's likeness was carved in its bas-relief over the entrance by sculptor Antoine Bourdelle and included in painted murals of the nine muses by Maurice Denis in the auditorium. In 1987, she was inducted into the National Museum of Dance and Hall of Fame.

Anna, Lisa,[71] Theresa and Irma, pupils of Isadora Duncan's first school, carried on the aesthetic and pedagogical principles of Isadora's work in New York and Paris. Choreographer and dancer Julia Levien was also instrumental in furthering Duncan's work through the formation of the Duncan Dance Guild in the 1950s and the establishment of the Duncan Centenary Company in 1977.[72]

Another means by which Duncan's dance techniques were carried forth was in the formation of the Isadora Duncan Heritage Society, by Mignon Garland, who had been taught dance by two of Duncan's key students. Garland was such a fan that she later lived in a building erected at the same site and address as Duncan, attached a commemorative plaque near the entrance, which is still there as of 2016[update]. Garland also succeeded in having San Francisco rename an alley on the same block from Adelaide Place to Isadora Duncan Lane.[73][74]

In medicine, the Isadora Duncan Syndrome refers to injury or death consequent to entanglement of neckwear with a wheel or other machinery.[75]

Photo gallery

[edit]- Photographic studies of Isadora Duncan made in New York by Arnold Genthe during her visits to America in 1915–1918

In popular culture

[edit]Duncan has attracted literary and artistic attention from the 1920s to the present, in novels, film, ballet, theatre, music, and poetry.

In literature, Duncan is portrayed in:

- Aleister Crowley's Moonchild (as 'Lavinia King'), published in 1923.[76]

- Upton Sinclair's World's End (1940) and Between Two Worlds (1941), the first two novels in his Pulitzer Prize winning Lanny Budd series.[77]

- Amelia Gray's novel Isadora (2017).[78]

- A Series of Unfortunate Events, in which two characters are named after her, Isadora Quagmire and Duncan Quagmire.[79]

- The poem Fever 103 by Sylvia Plath, in which the speaker alludes to Isadora's scarves.[80]

Among the films and television shows featuring Duncan are:

- In 1965, a youthful Isadora Duncan was portrayed by Kathy Garver in the television show Death Valley Days.[81]

- The 1966 BBC biopic by Kenneth Russell, Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World, which was introduced by Duncan's biographer, Sewell Stokes, Duncan was played by Vivian Pickles.[82]

- The 1968 film Isadora, nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes, stars Vanessa Redgrave as Duncan. The film was based in part of Duncan's autobiography. Redgrave was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance as Duncan.[82][83]

- Archival footage of Duncan was used in the 1985 popular documentary That's Dancing!.[84][85]

- A 1989 documentary, Isadora Duncan: Movement from the Soul, was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the 1989 Sundance Film Festival.[86]

- In 2016, Lily-Rose Depp portrayed Duncan in The Dancer, a French biographical musical drama of dancer Loie Fuller.[87]

Ballets based on Duncan include:

- In 1976 Frederick Ashton created a short ballet entitled Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan on Lynn Seymour, in which "Ashton fused Duncan's style with an imprint of his own"; Marie Rambert claimed after seeing it that it was exactly as she remembered Duncan dancing.[88]

- In 1981, she was the subject of a ballet, Isadora, written and choreographed by the Royal Ballet's Kenneth MacMillan, and performed at Covent Garden.[89]

On the theatre stage, Duncan is portrayed in:

- A 1991 stage play When She Danced by Martin Sherman about Duncan's later years, won the Evening Standard Award for Vanessa Redgrave as Best Actress.[90]

Duncan is featured in music in:

- Celia Cruz recorded a track titled Isadora Duncan with the Fania All-Stars for the album Cross Over released in 1979.[91]

- Rock musician Vic Chesnutt included a song about Duncan on his debut album Little.[92]

- The Magnetic Fields song "Jeremy" on their second album The Wayward Bus refers to Duncan and her "impossibly long white scarves."[93]

- Post-hardcore band Burden of a Day's 2009 album Oneonethousand features a track titled "Isadora Duncan". The lyrics include references to a letter Duncan wrote to poet Mercedes de Acosta and her reported last words of "Je vais à l'amour."

See also

[edit]- Dancer in a Café—Painting by Jean Metzinger

- Isidora, sometimes spelled Isadora

- List of dancers

- Women in dance

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c While Duncan's birth date is widely given as May 27, 1878, her posthumously discovered baptismal certificate records May 26, 1877. Any corroborating documents that might have existed were likely destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[1]

- ^ Desti helped Crowley write his magnum opus Magick (Book 4) under her magical name of "Soror Virakam", and also co-edited four numbers of his journal The Equinox, and contributed several collaborative plays.

References

[edit]- ^ Stokes, Sewell. "Isadora Duncan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ a b Craine, Debra; Mackrell, Judith (2000). The Oxford Dictionary of Dance (First ed.). Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-19-860106-7. OCLC 45663394.

- ^ a b c Deborah Jowitt (1989). Time and the Dancing Image. University of California Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-520-06627-4.

- ^ Genthe, Arnold (photographer). "Elizabeth Duncan dancer". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ^ Lilian Karina; Marion Kant (January 2004). Hitler's Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. Berghahn Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-57181-688-7.

- ^ Ean Wood, Headlong Through Life: The Story of Isadora Duncan (2006), p. 27: "They...would all be drowned, along with 104 others, when the S.S. Mohegan, en route from London to New York, ran aground on the Manacle Rocks off Falmouth, in Cornwall."

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 17

- ^ International encyclopedia of dance : a project of Dance Perspectives Foundation, Inc. Cohen, Selma Jeanne, 1920–2005., Dance Perspectives Foundation. (1st paperback ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-517369-7. OCLC 57374499.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Duncan (1927), p. 21

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 31

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 55

- ^ "Isadora Duncan | Biography, Dances, Technique, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 58

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 69

- ^ Daly, Ann (2002). Done into dance : Isadora Duncan in America (Wesleyan ed.). Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6560-1. OCLC 726747550.

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 94

- ^ Jowitt, Deborah. Time and the Dancing Image. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. p. 71

- ^ Kurth (2001), p. 155

- ^ Setzer, Dawn. "UCLA Library Acquires Isadora Duncan Collection" Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, UCLA Newsroom, last modified April 21, 2006

- ^ Abridged ed, p. 676.

- ^ Aleister Crowley, Magick: Liber ABA: Book 4: Parts 1–4 2nd revised ed. York Beach, ME, 1997, p. 197

- ^ The Untold Story: The Life of Isadora Duncan 1921–1927 (1929).

- ^ a b Aydt, Rachel (May 29, 2007). "Rediscovered". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on June 25, 2007. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ^ Sturges (1990), p. 39

- ^ Kurth (2001), p. 168

- ^ Duncan, Irma (1966). Duncan Dancer: An Autobiography. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 163–186. ISBN 9780819577931.

- ^ Kurth (2001), p. 392

- ^ Kurth (2001), pp. 365, 392

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (1977-09-22). "IRMA DUNCAN DEAD; DISCIPLE OF ISADORA (Published 1977)". The New York Times. p. 28. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved 2024-03-06.

- ^ "Isadora Duncan, 1877–1927: The Mother of Modern Dance". VOA. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ^ Sturges (1990), p. 120

- ^ Sturges (1990), pp. 121–124

- ^ Greg Daugherty (2 May 2013). "8 Famous People Who Missed the Lusitania". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 422

- ^ Aaron Greer (7 March 2016). "Varshavianka (1924)". Archived from the original on 2021-12-11 – via YouTube.

- ^ Stewart J, Sacred Woman, Sacred Dance, 2000. p. 122.

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 343

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 10

- ^ a b Duncan (1927), p. 75

- ^ Kurth (2001), p. 57

- ^ Duncan (1927), p. 45

- ^ a b Kurth (2001)

- ^ Gavin, Eileen A. and Siderits, Mary Anne, Women of vision: their psychology, circumstances, and success (2007), p. 267

- ^ "Isadora Duncan and Paris Singer". Dark Lane Creative. 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ Gerrie (2014-09-24). "The Linosaurus: Isadora Duncan: a taste for life". The Linosaurus. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ "Duse, Eleanora (1859–1924)". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. 2006-09-10. Archived from the original on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ S.A. Yesenin. Life and Work Chronology Archived 2016-09-18 at the Wayback Machine. The Complete Works by S.A. Yesenin in 7 Volumes. Nauka Publishers, 2002 // Хронологическая канва жизни и творчества. Есенин С. А. Полное собрание сочинений: В 7 т. – М.: Наука; Голос, 1995–2002.

- ^ Hugo Vickers, Loving Garbo: The Story of Greta Garbo, Cecil Beaton, and Mercedes de Acosta, Random House, 1994.

- ^ Schanke (2006)

- ^ Barnett, David (2024-03-02). "Mercedes de Acosta: The poet who had affairs with the 20th century's most famous women". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ "GarboForever - Garbo's letters to Mercedes de Acosta". www.garboforever.com. Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ Salter, Stephanie (April 20, 2000). "The proof is in Garbo's letters: The best is silence". SFGate.com. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ Cole, Steve (director) (2001). Greta Garbo: A Lone Star (Television production). American Movie Classics. 39.98–40.5 minutes in.

- ^ a b Dikovskaya, Lily (2008). In Isadora's Steps: The Story of Isadora Duncan's School in Moscow, Told By Her Favourite Pupil. Book Guild Ltd. pp. 25, 39, 48. ISBN 978-1846241864.

- ^ Gillies, Malcolm; Pear, David; Carroll, Mark, eds. (2006). Self Portrait of Percy Grainger. Oxford University Press. p. 116.

- ^ Milford, Nancy (1983). Zelda: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins. p. 118.

- ^ a b Sturges (1990), pp. 227–230

- ^ "DEATH By Flowing Scarf – Isadora Duncan, USA". True Stories of Strange Deaths. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Isadora Duncan Meets Fate". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Isadora Duncan killed in Paris under wheels of car she was buying". Sandusky Star Journal. September 15, 1927. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Isadora Duncan, Dragged by Scarf from Auto, Killed; Dancer Is Thrown to Road While Riding at Nice and Her Neck Is Broken". The New York Times. 1927-09-15. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Janet Flanner (1972-06-16), "Episode 179, Season 6", The Dick Cavett Show

- ^ "Affectations Can Be Dangerous". Three Hundred Words. Archived from the original on 2013-10-10.

- ^ Petrucelli, Alan (2009). Morbid Curiosity: The Disturbing Demises of the Famous and Infamous.

- ^ Kavanagh, Nicola (May 2008). "Decline and Fall". Wound Magazine (3). London: 113. ISSN 1755-800X.

- ^ Hemingway: The Homecoming

- ^ "Search Results: "Maria Theresa Duncan" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ^ "Search Results: "Anna Duncan" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Search Results: "Irma Duncan" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ^ Kateřina Boková. "100-year birth anniversary of Jarmila Jeřábková – dancer, choreographer and teacher". Czech Dance Info. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Search Results: "Lisa Duncan" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ^ Jennifer Dunning (September 9, 2006). "Julia Levien, 94, Authority on the Dances of Isadora Duncan, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (September 24, 1999). "Mignon Garland Dies at 91; Disciple of Isadora Duncan". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Journal of proceedings, Board of Supervisors, City and County of San Francisco". The Wayback Machine. Board of Supervisors, City and County of San Francisco. January 25, 1988. p. 89. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Gowens PA, Davenport RJ, Kerr J, Sanderson RJ, Marsden AK (July 2003). "Survival from accidental strangulation from a scarf resulting in laryngeal rupture and carotid artery stenosis: the "Isadora Duncan syndrome". A case report and review of literature". Emerg Med J. 20 (4): 391–3. doi:10.1136/emj.20.4.391. PMC 1726156. PMID 12835372.

- ^ Tobias Churton (1 January 2012). Aleister Crowley: The Biography: Spiritual Revolutionary, Romantic Explorer, Occult Master – and Spy. Watkins Media Limited. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-78028-134-6.

- ^ Upton Sinclair (1 January 2001). Between Two Worlds I. Simon Publications LLC. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-931313-02-5.

- ^ Schaub, Michael (25 May 2017). "A Dancer is Unstrung By Grief in 'Isadora'". NPR.

- ^ Kramer, Melody Joy (12 October 2006). "A Series Of Unfortunate Literary Allusions". NPR.

- ^ Dr Tracy Brain (22 July 2014). The Other Sylvia Plath. Routledge. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-317-88160-5.

- ^ Garver, K. (2015). Surviving Cissy: My Family Affair of Life in Hollywood. Globe Pequot. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-63076-116-5. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Ann Daly (1 March 2010). Done into Dance: Isadora Duncan in America. Wesleyan University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8195-7096-3.

- ^ Isadora at IMDb

- ^ John Cline; Robert G. Weiner (17 July 2010). From the Arthouse to the Grindhouse: Highbrow and Lowbrow Transgression in Cinema's First Century. Scarecrow Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-8108-7655-2.

- ^ Isadora Duncan at IMDb

- ^ Annette Lust (2012). Bringing the Body to the Stage and Screen: Expressive Movement for Performers. Scarecrow Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-8108-8212-6.

- ^ Keslassy, Elsa (September 24, 2015). "Lily-Rose Depp to Star as Isadora Duncan in 'The Dancer'". Variety. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Kavanagh J. Secret Muses: The Life of Frederick Ashton. Faber & Faber Ltd, London, 1996, p543.

- ^ "Isadora (1981 ballet)" on the Barry Kay Archive website. Retrieved: April 6, 2008

- ^ Carrie J. Preston (2011-08-08). Modernisms Mythic Pose: Gender, Genre, Solo Performance. Oxford University Press. pp. 293–294. ISBN 978-0-19-987744-7.

- ^ Angel G. Quintero Rivera (1989). Music, Social Classes, and the National Question of Puerto Rico. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. p. 34.

- ^ Peter Buckley (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-84353-105-0.

- ^ "The Magnetic Fields - Jeremy". Genius. 1992-01-01. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

Bibliography

[edit]- De Fina, Pamela. Maria Theresa: Divine Being, Guided by a Higher Order. Pittsburgh: Dorrance, 2003. ISBN 0-8059-4960-7

- About Duncan's adopted daughter; Pamela De Fina, student and protégée of Maria Theresa Duncan from 1979 to 1987 in New York City, received original choreography, which is held at the New York Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

- Duncan, Anna. Anna Duncan: In the footsteps of Isadora. Stockholm: Dansmuseet, 1995. ISBN 91-630-3782-3

- Duncan, Doralee; Pratl, Carol and Splatt, Cynthia (eds.) Life Into Art. Isadora Duncan and Her World. Foreword by Agnes de Mille. Text by Cynthia Splatt. Hardcover. 199 pages. W. W. Norton & Company, 1993. ISBN 0-393-03507-7

- Duncan, Irma. The Technique of Isadora Duncan. Illustrated. Photographs by Hans V. Briesex. Posed by Isadora, Irma and the Duncan pupils. Austria: Karl Piller, 1937. ISBN 0-87127-028-5

- Kurth, Peter. Isadora: A Sensational Life. Little Brown, 2001. ISBN 0-316-50726-1

- Levien, Julia. Duncan Dance: A Guide for Young People Ages Six to Sixteen. Illustrated. Dance Horizons, 1994. ISBN 0-87127-198-2

- Peter, Frank-Manuel (ed.) Isadora & Elizabeth Duncan in Germany. Cologne: Wienand Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-87909-645-7

- Savinio, Alberto. Isadora Duncan, in Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia. Bompiani,1942, Adelphi, 1984.

- Schanke, Robert That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta. Carbondale, Ill: Southern Illinois Press, 2003.

- Stokes, Sewell. Isadora, an Intimate Portrait. New York: Brentanno's Ltd, 1928.

- Sturges, Preston; Sturges, Sandy (adapt. & ed.) (1991), Preston Sturges on Preston Sturges, Boston: Faber & Faber, ISBN 0-571-16425-0

Further reading

[edit]- Daly, Ann. Done into Dance: Isadora Duncan in America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

- "Atlas F1 historical research forum about the Amilcar debate". 2002-07-21. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

External links

[edit] Media related to Isadora Duncan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Isadora Duncan at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Isadora Duncan at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Isadora Duncan at Wikiquote- "Isadora Duncan's Birthplace". Waymarking.com., 501 Taylor, San Francisco

Archival collections

- Isadora Duncan pandect – Everything on the greatest dancer of the 20th century.[permanent dead link] Dora Stratou Dance Theater, Athens, Greece.

- The Isadora Duncan Archive- a repository of historical and scholarly reference materials; artistic and archival collections; repertory lists with music; and videos of Duncan choreography. Created by Duncan practitioners, the IDA envisions many dancers, researchers, scholars, students and artists will greatly benefit from this continually expanding and non-commercial resource.

- Finding Aid for the Howard Holtzman Collection on Isadora Duncan ca. 1878–1990 (Collection 1729) UCLA Library Special Collections, Los Angeles, California.

- Digitized manuscripts from the Howard Holtzman Collection on Isadora Duncan, ca 1878–1990 (Collection 1729) hosted by the UCLA Digital Library.

- Guide to the Isadora Duncan Dance Programs and Ephemera. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Guide to the Mary Desti Collection on Isadora Duncan, 1901–1930. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Other

- Dances By Isadora, Inc.

- Dance Visions NY, Inc.

- Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation, Inc.

- Isadora Duncan Heritage Society Japan Archived 2012-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Isadora Duncan International Institute, Inc.

- Isadora Duncan International Symposium Archived 2019-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- isadoraNOW Foundation

- "Images related to Isadora Duncan". NYPL Digital Gallery. and Library of Congress image galleries

- Modern Duncan biographer, Peter Kurth's Isadora Duncan page

- 1921 passport photo (flickr.com)

- Isadora Duncan: Dancing with Russians Archived 2014-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ISADORA DUNCAN (1877–1927)

- 1870s births

- 1927 deaths

- 19th-century atheists

- 20th-century American dancers

- 20th-century atheists

- Accidental deaths in France

- American bisexual artists

- American atheists

- American autobiographers

- American women choreographers

- American choreographers

- American communists

- American emigrants to France

- American expatriates in the Soviet Union

- American female dancers

- Artists from San Francisco

- Bisexual women artists

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Communist women writers

- Dancers from California

- Free and improvised dance

- LGBTQ choreographers

- Bisexual dancers

- French LGBTQ dancers

- American LGBTQ dancers

- LGBTQ people from California

- American modern dancers

- Road incident deaths in France

- Writers about the Soviet Union

- American women autobiographers

- LGBTQ female dancers